You’ve probably heard of Malcolm Gladwell’s ‘10,000 hours principle’ – that to reach mastery in most things, it takes about 10,000 hours of practice.

Does this apply to music?

I would say that generally it does (in my opinion it can take quite a bit less when you practice the right things, but it does convey the overall idea – it will take time and effort).

But I want to discuss what I think those 10,000 hours of practice should consist of.

Most musicians hear ‘10,000 hours’ and assume that this means ‘10,000 hours sitting at your instrument’.

But as I mentioned in a previous post – only a small portion of my practice time has ever been spent sitting at my instrument.

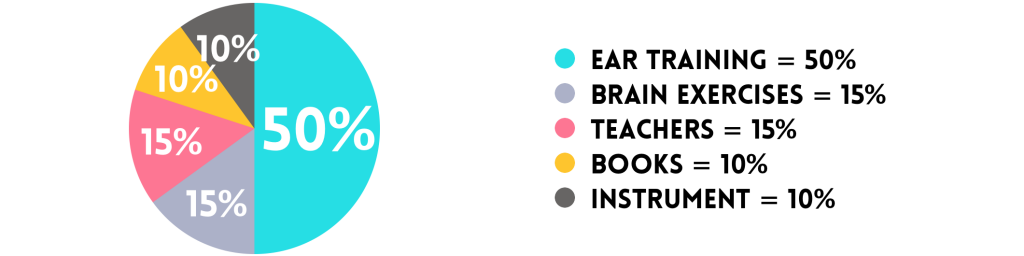

If I was to break down my practice time, from the last 20 years as a musician – it would look something like this:

– Ear training (transcribing songs by ear) = 50%

– Brain training exercises = 15%

– Learning with teachers (University / private lessons) = 15%

– Reading (books on music theory) = 10%

– At the piano = 10%

Lets breakdown each of these activities in detail:

Ear training (50%)

Most of my learning has come from figuring out songs by ear – known as ‘transcribing’.

Every time I hear music played, my brain starts transcribing. It’s a habit – I can’t turn it off, and wouldn’t want to.

On average, I probably hear 15 songs a day – if I’m video editing at a coffee shop, going to the gym, or doing anything in a public place – music will be playing, everywhere.

My brain is always doing the work, even when the music is in the background:

– I might be focussed on video editing, but I’m also figuring out every note and chord to the background music.

– I might be watching a film – but my brain is also transcribing the soundtrack.

– I might be on the rowing machine – but part of my brain is also transcribing the background music.

So most of my daily practice is ear training – and always will be. Even if I wanted to practice playing piano more than ear training – I couldn’t physically do it. There will always be more opportunities to transcribe music by ear, than there will be time I can realistically spend at the piano.

And the nice thing about ear training, is it fits into your life seamlessly. You don’t have to set time aside to practice it – it comes with you, everywhere you go.

So it’s easier than you might have thought to rack up 10,000 hours when part of your practice is ear training.

Brain Exercises (15%)

As I mentioned in a recent blog post, pretty much anything in music can be practiced in your mind.

Your instrument can be a huge set of distractions to your learning, as it requires you to do many things at once – read music, decide fingering, monitor technique, rhythm, dynamics, pedaling, etc. – and in many cases it can be more effective to practice things in your mind instead – where you don’t have these distractions.

Some of my favorite ‘thinking exercises’ include:

– ‘Interval arithmetic’ – Jump about the piano by random intervals in your mind – the faster you can do this, the faster your playing will be.

Click here to receive my ‘Interval Trainer’ MP3 tracks by email

– Compose in your mind – Think up interesting chord progressions to test out next time you’re at your instrument, new chord voicings you want to try – exploring new possibilities in your mind.

– Rehearse repertoire in your mind – Before you get up to play piano in public, run through the pieces you’re going to play in your mind first. How are you going to end each piece? Which songs will be in your set? Remind yourself of that tricky section you sometimes forget.

Brain exercises – like ear training – can also be done at anytime, away from your instrument, so this is another good way to rack up your 10,000 hours.

Teachers (15%)

I’ve learnt a lot of great things from some world class teachers over the years. But the key here is that they have to be the right teachers – not any teacher will lead to breakthroughs.

I had 3 very influential teachers that taught me a great deal, and I spent about 2 solid years with each.

I suggest trying a range of teachers – and when you feel that you’ve learnt everything you’re going to learn from one teacher, it’s time to look for someone new.

Reading (10%)

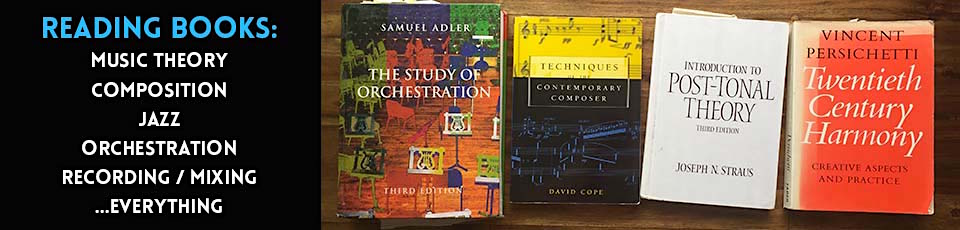

I’ve learnt a great deal from reading music theory books. Despite being the slowest reader in the world, I have enjoyed reading a lot of books on music.

The books I’ve read are mostly on music theory, composition techniques, orchestration, and jazz piano. While at university I was completely obsessed with learning everything I could about music, and I used to search through the books in the library and read everything – old and new.

To name a few of my favorite books:

– ‘The Jazz Piano Book’ by Mark Levine.

– ’20th Century Harmony’ by Vincent Persichetti.

– ‘Introduction to Post Tonal Theory’ by Joseph Strauss (very geeky)

– ‘The Study of Orchestration’ by Samuel Adler (for orchestral composers)(very geeky)

– ‘Sound On Sound Magazine’ (for music mixing / producing)

My reading got a bit out of control at one point – I’m probably one of very few people who’s read the ‘Logic Pro 9 instruction manual’ from cover to cover (‘Logic’ is a type of music making software). The manual is huge, something like 700 pages, but it taught me the best practices of how to record and produce music electronically.

So I believe that reading is an essential part of your learning. It’s hard to go wrong with music theory books – usually you’ll learn from any book you choose to read.

At The Piano (10%)

And a surprisingly small (but still important) part of my development has taken place at the piano.

My time at the instrument is usually spent doing one of two things:

1. Composition / exploration. My main goal in music is composition – writing my own music – so I use my piano time to look for new possibilities within the 12 notes that I haven’t played before. Even after 20 years of playing, I know that there’s many things I’ve not yet discovered.

2. Technique practice. I work on my technique by playing REAL PIECES – pieces that challenge me to improve my technique, while also being enjoyable to play.

Focus on one thing at a time

It’s important for me to add, that what I practice fluctuates. The above breakdown represents my 20 years of learning as a whole – but if I was to breakdown each day, it would be focussed on one of these areas at a time.

In fact, I’ll usually stay focused on one of these areas for several months on end – reading for 3 months, then technique for the next 4 months, and lessons for 6 months after that.

The only activity that I consistently practice everyday – is ear training. Because that’s something I can’t get away from – there will always be music playing around you (unless you live under a rock),

Your Practice Might Look Different

Remember – this is just a breakdown of MY ‘10,000 practice hours’ – every musician’s will look slightly different, depending on your goal.

My goal was always composition – so I did a lot more reading than most.

But for a musician who’s goal is to be a performer – they’d probably play their instrument more (but not that much more), and there’d be less brain exercises perhaps.

So as with my previous post on ‘thinking practice’ – I’m not telling you to reduce your time at your instrument. I’m just emphasizing the importance of also practicing music in your mind, away from your instrument – and just generally immersing yourself in music every single day. Music is all around you.

Thank you for reading. I hope this gave you new ideas to what your practice can be. Is there an area in this list that you’ve been neglecting? What’s the one thing you need to work on most?

Enjoy your practice, and I’ll see you in the next post!

– Julian Bradley