In music, ‘spelling’ refers to how you label notes – ‘F#’ or ‘Gb’? ‘C natural’ or ‘B#‘ or even ‘D double flat’?

Correct note spelling is a common area of confusion. There is a proper way to spell notes, and by following the convention your music will be clear and easy for musicians to read.

In this lesson I explain everything you need to know for most situations.

CONVENIENCE

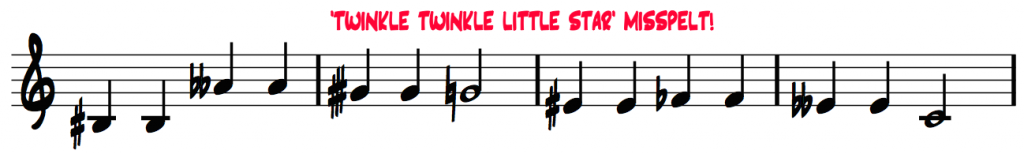

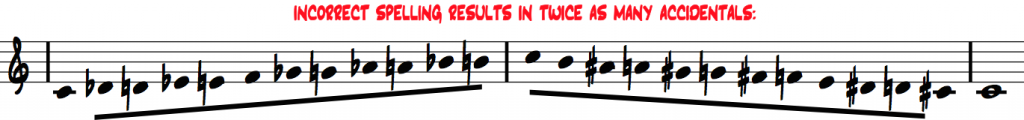

Any note can be spelt multiple ways. Look at how unnecessarily complicated I’ve made ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’ look due to bad spelling:

Most of the time spelling isn’t a problem – you sort of know how to spell most notes. But sometimes you’ll encounter an odd situation when spelling becomes a problem.

Basic Guidelines

Before we go into depth, here are my basic guidelines for spelling notes:

1. Stick to all sharps, or all flats if you can. Things get confusing when you see a variety of sharps and flats in the music.

2. Use the fewest accidentals possible. If you have to choose between spelling the scale with 4 flats, or 7 sharps – go with 4 flats.

3. Avoid doubling letters – just use one type of C, one type of D, one E, etc. Avoid using 2 types of letter in your scale, like Db and D#. If your scale has 7 notes, then you’ll be able use one letter per note – C D E F G A B.

DIATONIC NOTE SPELLING

To spell your music correctly, first you have to know which scale your music is in.

If you’re writing music in the major or minor scale, a first step would be to identify which key you’re music is in – since the key signature will tell you how your music should be spelt – for example Bb major = 2 flats – Bb + Eb (not A# + D#). Click here to see my Key Signatures Lesson.

But what if you don’t already know how a key signature spells its accidentals (as sharps or flats?) – here’s how you can figure out a major or minor scale’s spelling from scratch:

How To Build Any Major Scale From Scratch:

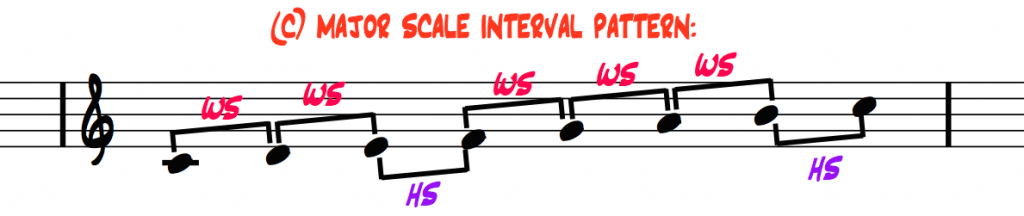

You’ve memorized the interval pattern of the major scale (WS – WS – HS – WS – WS – WS – HS):

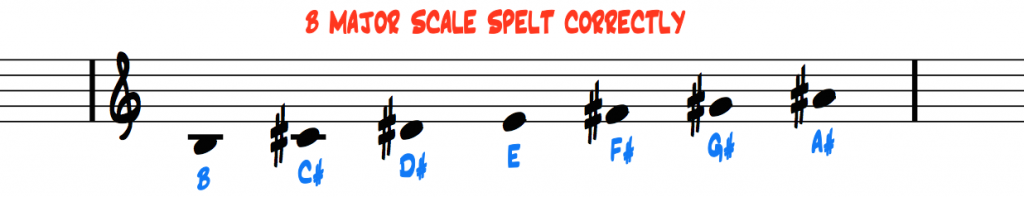

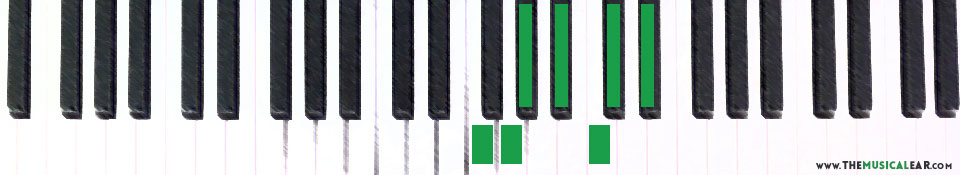

Map out this pattern starting from the root note of your scale – lets take ‘B major’ for example.

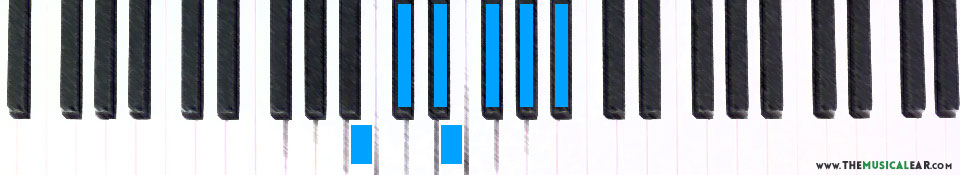

Don’t worry about spelling at first – just find the notes on the piano / in your mind:

B – up a whole-step = C# / Db – up a whole-step = D# / Eb – up a half-step = E – up a whole-step = F# / Gb – up a whole-step = G# / Ab – up a whole-step = A# / Bb.

Once you’ve found the notes, now spell them correctly:

Important: Each note needs to move up by one letter (B C D E F G A), and you want to avoid any doubled letters – only one type of B, only one type of C, one type of D, etc. You don’t want 2 of any letter (e.g. Cb and C# would be incorrect).

Start by ‘pinning down’ the root of the scale in place. For B major scale, we’ll pin down B first. Then we make sure that each note moves up one letter (B C D), and we’ll teak any notes with sharps or flats when needed:

– That means the 2nd will be spelt ‘C#’ (not Db) – because C is one up from B.

– The 3rd will be spelt ‘D#’ (not Eb) – because D is one up from C.

– The 4th will be spelt ‘E’ – because E is one up from D.

– The 5th will be spelt ‘F#’ (not Gb) – because F is one up from E.

– The 6th will be spelt ‘G#’ (not Ab) – because G is one up from F.

– The 7th will be spelt ‘A#’ (not Bb) – because A is one up from G … and we’ve already used ‘B’ for the root, so we don’t want 2 types of B in the scale).

How To Build Any Minor Scale From Scratch:

Follow the same process to figure out how to spell a minor scale:

- Pin down the root note.

- Map out the scale’s interval pattern (without worrying about spelling)

- Spell the scale making sure each note moves up a letter (C D E).

- Tweak with sharps / flats when needed.

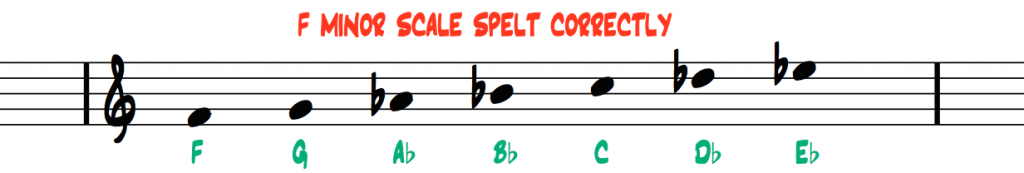

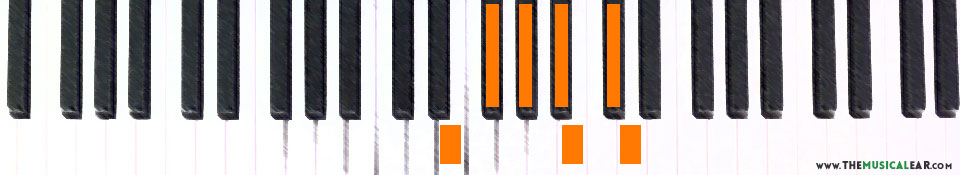

Lets try building the notes of F minor scale from scratch (the ‘natural minor’ scale):

1. Pin down the scale’s root note – F.

2. Build the minor scale’s interval pattern (WS – HS – WS – WS – HS – WS):

F – up a whole-step = G – up a half-step = G# / Ab – up a whole-step = A# / Bb – up a half-step = C – up a half-step = C# / Db – up a whole-step = D# / Eb.

3. Next figure out the spelling. Each note has to move up one letter at a time – F G A B C D E – and we’ll tweak with sharps or flats when needed:

The 2nd will be spelt ‘G’ – because G is one up from F (no tweaking needed).

The 3rd will be spelt ‘Ab’ (not G#) – because A is one up from G.

The 4th will be spelt ‘Bb’ (not A#) – because B is one up from A.

The 5th will be spelt ‘C’ – because C is one up from B (no tweaking needed).

The 6th will be spelt ‘Db’ (not C#) – because D is one up from C … and we’ve already used one type of C).

The 7th will be spelt ‘Eb’ (not D#) – because E is one up from D … and we’ve already used one type of D).

How To Build An Exotic Scale From Scratch:

The same process works for virtually any type of 7 note scale. All you have to know is the scale’s interval pattern (which is how you learn scales in the first place).

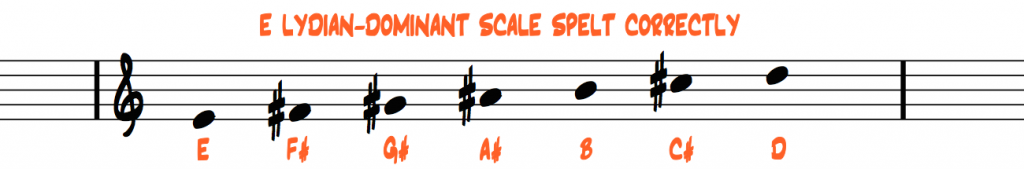

Lets take an exotic example – and figure out the notes of E lydian-dominant scale.

1. Pin down the scale’s root note – E.

2. Build the lydian-dominant scale’s interval pattern (WS – WS – WS – HS – WS – HS), without worrying about spelling yet:

E – up a whole-step = F# / Gb – up a whole-step = G# / Ab – up a whole-step = A# / Bb – up a half-step = B – up a whole-step = C# / Db – up a half-step = D.

3. Figure out the spelling. Each note has to move up one letter at a time – E F G A B C D – and we’ll tweak with sharps or flats when needed:

– Pin down ‘E’.

– The 2nd will be spelt ‘F#’ (not Gb) – because F is one up from E.

– The 3rd will be spelt ‘G#’ (not Ab) – because G is one up from F.

– The 4th will be spelt ‘A#’ (not Bb) – because A is one up from G.

– The 5th will be spelt ‘B’ – because B is one up from A (no tweaking needed).

– The 6th will be spelt ‘C#’ (not Db) – because C is one up from B.

– The 7th will be spelt ‘D’ – because D is one up from C.

Very Important: Sharps and flats don’t always end up being black notes. When you follow this process, sometimes it’s correct to spell a note as ‘B#’, or ‘Fb’, or even ‘Cb‘, or ‘E#‘. The note letters have to go up one at time in step – no matter what.

SHARPS OR FLATS?

Some keys come with the choice to use sharps or flats, depending how you choose to spell the root note. E.g. you could spell Ab major scale as ‘Ab major’ or ‘G# major’ – depending if you spell the root as Ab or G#.

So how do you decide which of these 2 spellings to use?

Normally you’d go with the spelling that has fewest accidentals. E.g. Ab major has 4 flats (Ab Bb Db Eb), and G# major has 7 sharps (G# A# B# C# D# E# F#) – so it would make sense to use Ab major in this case (unless you really don’t like your performers!).

If you’re choosing between C# major and Db major – C# major has 7 sharps (C# D# E# F# G# A# B#), and Db major has 5 flats (Db Eb Gb Ab Bb) – so it would make sense to use Db major in this case.

If you’re choosing between F# major and Gb major – F# major has 6 sharps (F# G# A# C# D# E#), and Gb major has 6 flats (Gb Ab Bb Cb Db Eb) – in this case we’re split, so the choice is yours.

However, there’s one additional factor to consider…

WHICH INSTRUMENTS ARE YOU WRITING FOR?

The instruments you’re writing for can also effect your choice of key / spelling:

String players (violins, cellists, guitarists, etc) tend to prefer keys spelt with sharps. This is because when a string player presses down a fret, the note is sharpened – so they’re already in the upward mindset of sharpening notes:

Wind players (trumpet, saxophone, flute, etc) tend to prefer flat keys. This is because when a wind player presses down a key, the note is flattened – so they’re already in the downward mindset of flattening notes:

However this is something you’d probably consider earlier in the composition phase. If you’re writing for a string ensemble, choose a sharp key like G major, D major, A major. If you’re writing for a wind ensemble, choose a flat key like F major, Bb major, Eb major (many wind / big band arrangements are written in these keys for this reason).

PROBLEMATIC SCALES

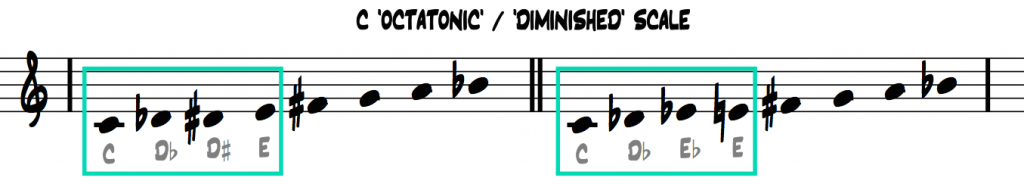

For 99% of situations, you’ll be fine using the above guidelines for note spelling. The place that spelling tends to go out of the window is with scales that have more than 7 notes – since there’s not enough note letters for each note to have its own letter – you’ll end up with 2 types of one note somewhere (e.g. Db and D#).

Common scales that have this problem are the octatonic scale (aka diminished scale), which has 8 notes:

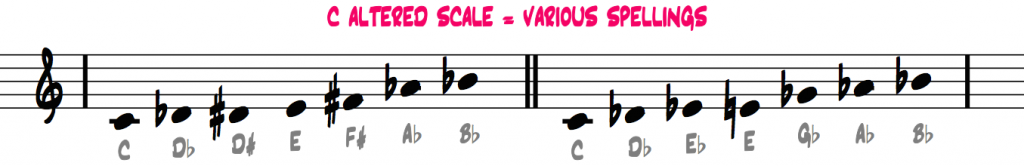

The altered scale is also tricky to spell, although it only has 7 notes) :

I’ve seen these scales spelt a variety of ways, and I don’t believe there’s a definitive rule yet. If you use these scales, just try to spell them as simply as possible, based on the situation.

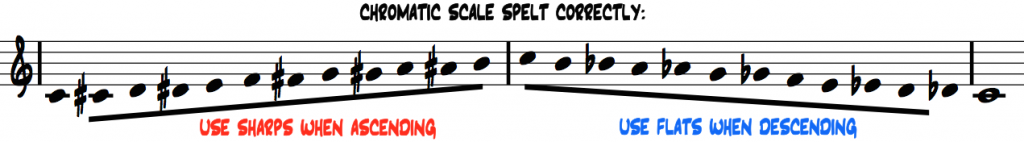

And then there’s the chromatic scale, which has all 12 notes. When notating the chromatic scale, use sharps when the melody is ascending, and flats when descending:

This way you’ll save yourself having to use natural signs after each sharpened / flattened note:

Free Giveaway

Thanks for reading. As a music educator, I believe one exercise to be more important than all others. Click below to take my ‘interval trainer challenge’ and see if you can pass all 3 of my Interval Trainer MP3 tracks: